A week or two ago, I was on a call with a well-known, national news outlet.

We were walking them through one of our products we call BYOL—Bring Your Own License. In this model, we allow users to carry their publisher provided licenses to their preferred AI outlets.

Midway through the conversation, the person on the other end paused and said,

"Hold on. Are you saying that instead of the broad licensing deal we did recently with one of the major AI companies—where we handed over access to our entire archive—we could’ve kept our direct relationship with readers, let them carry their subscriptions into those AI apps, and still gotten paid?"

“Yes," I said, “that’s exactly what I’m saying”.

I could see on this person’s face, they were flabbergasted. The thought this was even possible hadn’t even crossed their mind.

It’s not surprising, and to any keen observer, it should be obvious that publishers are playing directly into a playbook that has been well established and demonstrated over the last few decades between big tech and publishers. It goes like this:

- New tech platform enters the scene. It needs content, credibility, and users. So they do deals—good deals, even generous ones, with well-established publishers who are paid to bring their content and audiences into the new ecosystem.

- The tech platform grows. As it grows, renewal deals with publishers diminish in size, scope, and frequency.

- The rug is pulled. The money dries up, and publishers, who were once paid to contribute, are now expected to give their content away for exposure, or worse, pay for exposure themselves.

This pattern is well documented, as we’ll see in this article. However, I’d argue this time, it’s different than every other epoch before.

Historically, publishers have been able to rely on the “click”. If they could get users to click on links, whether via a search engine or a referring link, they could figure out how to monetize it. AI is moving us towards a Zero Click Internet, and it breaks all of the rules every publisher has come to rely on for the last 30 years.

As such, publishers need to take a pro-active approach to determining their fate—any publisher who thinks they can wait and figure this one out like they have before is quickly going to find themselves on the wrong side of history.

A Brief History of the Rug Pull

This is not a new playbook between Big Tech and Publishers. The examples I provide below illustrate a consistent pattern over the last 30 years.

1. AOL’s Walled Garden

The Platform Needs Publishers In the mid-1990s, AOL paid publishers to distribute news and articles inside its proprietary platform. It was a clean, curated interface—and AOL needed premium media brands to lend it credibility and fill it with content.

The Platform Gains Power As AOL’s user base ballooned to over 26 million subscribers by the late '90s, it no longer needed publishers to draw traffic. The content was there, the users were loyal, and AOL was the dominant consumer internet gateway.

The Rug Pull Once dominant, AOL cut deals, deprioritized partners, and leaned into unpaid community content like message boards and chatrooms. Publishers were pushed out, and the value proposition disappeared.

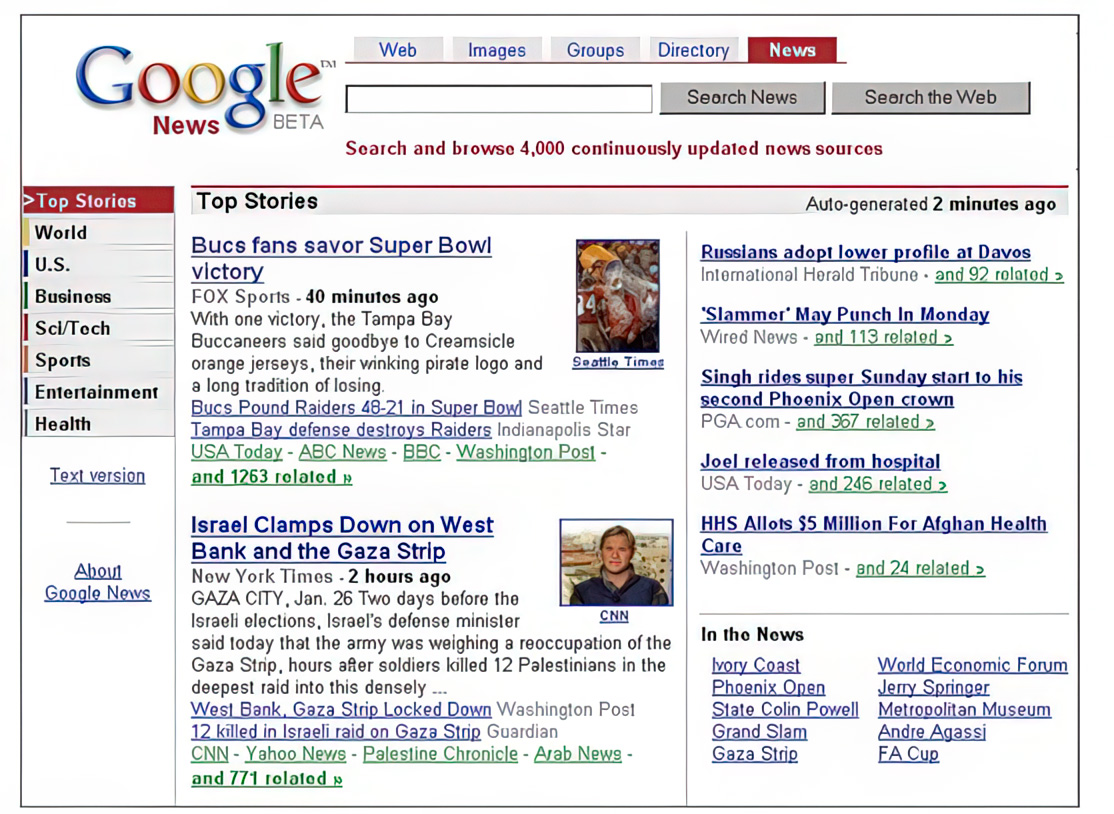

2. Google News

The Platform Needs Publishers When Google News launched in 2002, it scraped and aggregated publisher headlines and snippets to power discovery. In some regions like France and Australia, regulatory pressure led Google to sign licensing deals to pay publishers for content.

The Platform Gains Power As Google’s dominance over web discovery grew, publishers became increasingly dependent on Google for traffic. SEO became a discipline of its own, and content strategies shifted to appease the algorithm.

The Rug Pull The payments slowed or stopped altogether for many. Today, publishers spend millions optimizing for visibility in Google’s ecosystem—essentially paying for a shot at traffic from a feed that once compensated them. Meanwhile, Google remains the gateway to the internet for billions of users and continues to grow its advertising empire.

3. Facebook Live

The Platform Needs Publishers In 2016, Facebook paid over $50 million to publishers and public figures to adopt Facebook Live. Media outlets hired teams, launched shows, and adapted workflows around the format.

The Platform Gains Power Live content drove engagement. It was prioritized in the feed. Facebook trained users to expect real-time content—and trained publishers to deliver it.

The Rug Pull Once established, Facebook pulled the funding. Live lost its algorithmic boost for publishers, and the teams built around it were dismantled. The traffic vanished overnight.

4. Medium’s Publisher Program

The Platform Needs Publishers Medium launched its Partner Program in 2017, offering minimum guarantees, editorial support, and revenue-share to publishers like The Awl, Ringer, etc.

The Platform Gains Power Medium pivoted to its own subscription model, deprioritizing publisher revenues in favor of its “open paywall.”

The Rug Pull In early 2018, Medium abruptly canceled publishing partner guarantees and support; many dropped out.

In every case, the story is the same: Platforms needed publishers—until they didn’t.

This Time Is Different

The rug pull is already underway again, this time with AI companies.

They’re doing bulk licensing deals with publishers—good money, wide access, multi-year terms. But these deals aren’t the future. Even in my conversation with the national news outlet, they said it themselves, “We’re doing these deals now, but honestly, we don’t even know if this is sustainable—will we even be around in 3 years?”

These deals aren’t a means to an end where the publisher can survive if they can just weather the storm a bit longer—it could literally be the end for many of them if they don’t play their cards right.

The reason this storm isn’t like the ones before is because AI doesn’t send traffic back. Which means, they need to figure the solutions out now, or these last content licensing deals may be the last ones they do.

When Google rose to power, it at least linked out. You could publish an article, get it indexed, and hope to capture traffic. Traffic meant pageviews. Pageviews meant ad revenue, subscriptions, donations, or product sales. There was a way to make the math work.

But LLMs don’t work that way.

When you ask an AI question, it answers it in-line. No click. No visit. No pageview. No monetization in the tried-and-true channels.

Cloudflare recently shared that LLMs crawl up to 71,000 pages for every one click they drive. The old web model—Publish → Index → Search → Click—is collapsing.

And if content creators aren’t getting traffic, they can’t monetize. And if they can’t monetize, the incentive to create dries up.

So Why Create?

This is the question nobody wants to say out loud—but everyone is starting to ask.

If AI breaks the click, and there’s no traffic…If there’s no traffic, there’s no revenue…If there’s no revenue, what’s the point?

Historically, people have created content for two reasons:

- To make money — via ads, subscriptions, paywalls, products

- To get attention — build a brand, grow influence, spark ideas (it’s why I’m writing this article!)

AI threatens both.

When users get answers in-line—without attribution, without citation, without links—publishers lose the audience. They lose the funnel. They lose the ability to monetize or even be noticed.

In a recent Axios Live interview, Cloudflare CEO Matthew Prince put it bluntly:

“I’m deeply, deeply worried that if we don’t solve this problem, the internet is going to die.”

He’s right.

The incentive structure that has powered the web for 30 years is disappearing.

Without a way to get noticed—or get paid—why would anyone keep creating?

The Fix: Content Must Be Paid For, Always

This is the heart of it.

If content is being used, it must be paid for. Period.

Not someday. Not maybe. Not through exposure or good karma or vague promises of “training value.”

Content must be metered, tracked, and compensated at the point of use.

And thankfully, two models are already starting to emerge that will make this possible.

1. Metered data consumption

One way forward is metered data consumption. In this model, AI usage of content is logged, tracked, and paid for—like utilities. When an LLM consumes content—whether it’s documentation, a blog post, a book, a journal, or a wiki—the interaction triggers a micropayment. Simple. Transparent. Fair.

Cloudflare’s Pay-Per-Crawl model is a concrete example of this approach. They allow publishers to set terms, require API keys, and charge fractional amounts per query. It turns passive scraping into real-time microtransactions. For publishers that historically relied on organic traffic, this provides a lifeline. A bridge from pageviews to paid queries.

What makes this model powerful is that it doesn’t require publishers to re-architect their business. No new product lines. No complex access rules. Just one principle: if you use the data, you pay.

But the big question remains: who pays?

Ultimately, there are only two options:

- The AI platform pays directly—either out of pocket or as a proxy for advertisers funding the AI platform.

- The end users pay for access—either through subscriptions or usage-based models.

In either case, metered consumption introduces accountability. Whenever a user wants documentation to power an answer, their query triggers a fee. If the AI platform wants reliable, structured knowledge from a publisher, it pays to use it.

This is not just about economics—it’s about respect. If content has value, it should be valued at the moment it’s used.

2. Bring Your Own License (BYOL)

BYOL is the other side of the coin. It’s built for premium publishers—those with real user bases, paywalls, and subscription models.

Rather than licensing an archive outright or blocking AI entirely, BYOL enables publishers to bring their users with them. A subscriber who pays for The Atlantic or The Economist or Wiley doesn’t lose access when they switch interfaces—they carry that access into AI tools like ChatGPT, Claude, or Perplexity.

The AI platform gets high-quality, trusted content. The user gets continuity. And the publisher keeps the relationship.

This is exactly what Cashmere is enabling publishers like Wiley to do today. Through integrations like Perplexity, Wiley’s content becomes accessible to AI users—but only if those users have a valid subscription.

It’s not just about access. It’s about control. It’s about identity.

Publishers don’t lose their audience. They don’t become a faceless footnote inside someone else’s answer box. They maintain their brand. Their funnel. Their economic model.

This is what long-term sustainability looks like.

Control, Monetization, Identity

BYOL isn’t just about payment. It’s about identity.

In a world where websites lose traffic and portals die, identity is all publishers have left. It's the last direct line to the audience. And if that goes? So does the leverage.

When I told the national news outlet about BYOL, I wasn’t just describing a clever monetization tool. I was describing a future where they didn’t have to surrender their relationship with readers. Where they didn’t have to bet everything on a disappearing wave of one-time licensing revenue. Where their brand could show up—inside AI apps—not as a ghost in a citation, but as a living, breathing presence.

BYOL preserves that line. It ensures the publisher retains the user relationship. It empowers them to set the terms of access. It allows them to build brand equity—even inside AI interfaces. And it monetizes not just content, but connection.

This is what Cashmere is building: a secure bridge between publisher IP and the AI economy. A way for publishers to be present in the future—without being erased by it.

Don’t Let the Pattern Repeat

The blueprint has already played out—over and over again.

This isn’t a warning about what might happen. It’s a reminder of what has already happened.

And this time, there’s no reset button. No clicks. No fallback plan.

If you’re a publisher reading this, ask yourself: Are you building a future where you still own your audience? Or one where you’re invisible inside someone else’s product?

We’re helping publishers take action. If you're ready to defend your content, your identity, and your economic model—reach out.

Let’s not wait for history to repeat. Let’s Write the Future together.

.jpg)